This article can be downloaded here (pdf, 208 kB).

Intercultural Management – the Art of Resolving and Avoiding Conflicts between Cultures

An article originally written in 1996 by Stuart D.G. Robinson

1. Introduction

‚Culture‘ is a fluid, multi-dimensional, process-type of phenomenon, which does not lend itself easily to linear representation. This also applies to the topic of intercultural management, as will be seen in the following pages through the numerous cross-references. In their book entitled ‚Culture and Negotiation‘, Faure and Rubin write:

Some people find the topic of culture so intangible or over-used that they prefer to avoid it. Others, who can accept the ambiguities, complex interdependencies and open ends, see the study of culture as an exciting exploration into one of the most dynamic and far-reaching aspects of human co-existence. An appreciation of culture is obviously one of the first steps towards understanding intercultural management.

2. Serious deficits: Where are high levels of intercultural competence urgently needed and why?

2.1 What does the term ‚culture‘ mean?

In the field of intercultural management, the term ‚culture‘ is sometimes defined as:

This definition is in fact more complex than it might at first appear.

Firstly, the term ’system‘ is used to indicate that the values which co-occur in a culture interact in a fairly rigid way. Accordingly, a culture is a rigid constellation of interactions between certain values. The rigidity of this system explains why some people regard culture as a ‚prison‘, i.e. something which is so rigid that it is virtually impossible to get in or out of it.

Secondly, the phrase ‚commonly share(d)‘ stipulates that the members of a culture must share a set of values, but it does not stipulate that every person must have only these values. On the contrary, it is assumed that a culture is made up of people who have some values in common, and others not: people constitute a culture only through the fact that they have a certain system of values in common. In other words:

This means that a person can be part of more than one system simultaneously. This is the case for most people, of course – a fact which contributes to the complexity of the phenomenon of culture.

Thirdly, the definition does not specify where the boundaries of a culture are. This allows for people who live in the same part of the world or in different parts of the world to belong to the same culture. They are not precluded from living in the same country, but this need not be the case. In other words, people who belong to the same religion, to the same academic discipline, to the same occupation, to the same company, to the same ethnic group, to the same political party etc. can constitute a culture – on the condition that they share the same system of interactions between values.

Fourthly, it is possible for people to experience a conflict inside themselves which results from two or more cultural systems which exist side-by-side within them and which are difficult to reconcile with one another. People often find themselves in internal value-conflicts, e.g. between their family origins and their working lives, between their attitudes to material wealth and their concerns about the environment etc.

Finally, it needs also to be observed that a person’s membership of a given culture is not fixed in terms of time. This leads to another pair of insights:

a culture can change.

Both individuals and cultures are to be treated as dynamic, living beings. A culture is not something static, but is both the catalyst and the victim of a continuous process of change.

2.1.1 Extending the concept of ‚culture‘

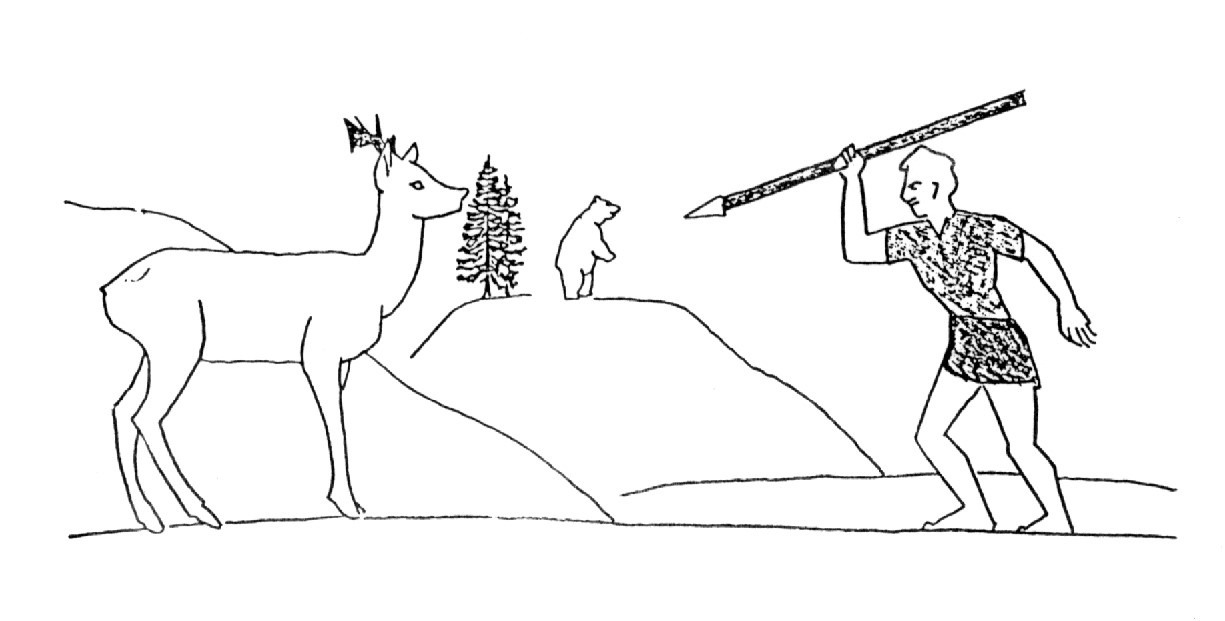

Research has shown that different groups of people structure their perceptions in different ways.3 Taking a well-known example, the picture below can be processed with or without the use of perspective.

A picture which can be interpreted with and without perspective

When this picture is shown to members of different ethnic cultures and they are asked which animal the hunter is pointing his spear at, they give different answers. Adults in mid-european cultures tend typically to say that it is the deer. When asked how they arrive at this answer, they reason that the deer is nearer. In certain other cultures, people might answer that it is the bear, or even the deer; but in their explanations they give reasons which have nothing to do with the relative size of the animals, nor the distance between them. In these types of cultures, the concept of two-dimensional perspective – which has only been widely used in mid-Europe for the last few hundred years – is ‚missing‘. For them, the relative size of visually represented objects has nothing to do with the distance between them. People do not come into the world with a concept of two-dimensional perspective; they only learn it if they are exposed to it – which is not the case for all people in the world.

Just as with this example of two-dimensional perspective, people’s cultural environments expose them to a whole variety of perception-norms which condition their interactions with the world. The systems of values which people share are based on such underlying perception-systems. The latter determine, first of all, what is perceived, and then how the perception process continues. Only when something has been perceived and has been structured in a certain way can it be assigned a value. Since the assignment of values pre-requires perception, the first definition of ‚culture‘ needs to be extended. ‚Culture‘ is now defined as:

or

This extension of the definition is essential in order to fully appreciate both the phenomenon of ‚culture‘ and one of the central aspects of ‚intercultural management‘ (see Section 5.1).

2.2 ‚Surface-culture‘ and ‚deep-culture‘

When one compares two different national cultures, e.g. those of Scotland and Malawi, one realises that many differences between these cultures are readily noticeable. A Scottish person getting out of an aeroplane in Malawi will immediately notice that the way people dress, the things they eat and the music they listen to are quite different to things in Scotland, and vice versa. As the Scottish person gets more acquainted with the ‚foreign‘ culture, he/she will begin to notice more subtle differences concerning behavioural norms and may even begin to adopt some of the local practices. Differences which are readily perceived will henceforth be termed ’surface-culture differences‘. The latter are to be found not only in relation to ethnic cultures but also in relation to all other types of cultures, e.g. age groups, religions, departments in companies and so on.

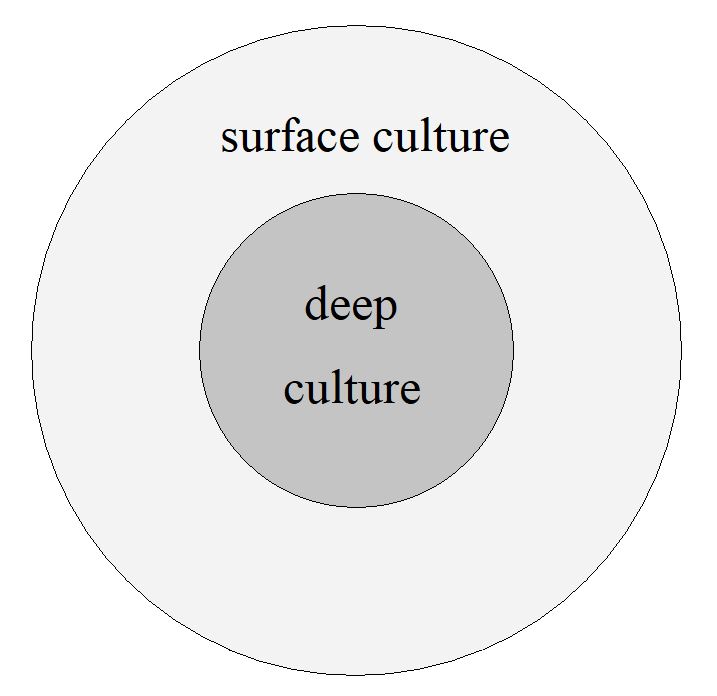

Levels of cultural differences

Although it is important to be aware of such surface-culture differences when interacting with people from other cultures, it needs to be stressed that these kinds of differences only play a minor role in intercultural relationships. It is the ‚deep-culture‘ differences, on the other hand, which can seriously endanger, or even sabotage, a long-term intercultural relationship (see Section 3.2 & 3.3).

‚Deep-culture‘ is the hidden part of culture which cannot be accessed directly by the human sensory organs. Deep-culture cannot be seen, cannot be heard, cannot be smelt or tasted. It comprises those cultural factors which are active in relationships, but which cannot readily be identified or understood. The factors which contribute to deep-culture differences are as difficult to recognize in oneself as they are in others. This is why they are of such significance and of such potential danger.

The realm of deep-culture has been examined by a number of researchers like Hofstede, Hampden-Turner, Trompenaars and others.4 This research goes back over many years, with a particular upsurge in the last three decades.

Deep-culture is hardly perceivable perhaps because it lies at the very roots of perception. What people perceive is determined by their deep-culture. One could even go so far as to say that deep-culture leads to a distortion of reality. However, it would be more precise to say that deep-culture is the source of the inaccurate re-structuring which takes place when things emanating from one culture are perceived by people from another. Their re-structuring is ‚inaccurate‘ because of the self-referential nature of human perception.

2.3 What is intercultural competence?

At the place where cultures meet, an interface is created which can often be full of misunderstandings and conflicts. It is contended5 that people who are involved in some way with cultural interfaces should possess high levels of intercultural competence (see Section 2.4). They require the ability:

- to put themselves into the position of members of another culture,

- to understand the ’surface-‚ and ‚deep-culture‘ differences and

- to mediate in interactions with that culture (see Sections 3.2, 4.1, 5.1).

To put oneself in the position of the member of another culture pre-requires that one is able to put oneself in the position of people within one’s own culture, i.e. including those who think quite differently to oneself. This means that one needs a high level of social competence as a pre-requisite for intercultural competence.6

From social to intercultural competence

2.3.1 Social and intercultural competence

Social and intercultural competence are the fundamental attitudes which a person genuinely possesses towards other people generally. These types of competence do not vary in level from one situation to another; they are constant and only change in a person very slowly over time. They are not intellectual kinds of attitudes which can be acquired cognitively.7 They cannot be simulated convincingly, nor can they be applied consciously, e.g. in order to manage people. The statement: ‚I am now going to display a high level of intercultural competence‘ is therefore a very different use of the words ‚intercultural competence‘. Working at a cultural interface has little to do with exercising power over other people or manipulating them to do things for one’s own purposes (see Section 4.2); instead, it involves facilitating communication between the cultures involved without becoming a further disturbance factor through one’s own presence and culturally-conditioned misinterpretations.

The levels of social and intercultural competence which different people possess vary widely. Most people are prepared to tolerate a certain degree of ‚different-ness‘ in others and to treat them as equivalent (i.e. to themselves). It follows that the different-ness of other people will lie either within or outside one’s personal tolerance boundary.

‚Social competence‘ is defined here as:

‚Intercultural competence‘ is defined as:

The difference between social and intercultural competence lies merely in the definition of different-ness. Different-ness in the context of social competence concerns differences between people which arise from their personality structures, their thinking-styles8, their appearance etc., but excludes differences which arise from their membership of different cultures. Different-ness in the context of intercultural competence comprises all those differences which arise from differing perception- and value-systems: in other words, which are caused by membership of different ethnic or non-ethnic cultures.

Since cultural differences and cultural interfaces arise everywhere – even in one’s closest vicinity – intercultural competence is something which most people and most relationships can benefit from.

In the definitions of social and intercultural competence, the word ‚acceptance‘ was used in preference to ‚tolerance‘. The latter is sometimes used in the sense of ‚tolerating‘ other people in society who are different; one accepts the down-sides of living alongside people who differ from ‚the norm‘. To ‚tolerate‘ people in this sense is to measure them with one’s own yardstick and to conclude that they do not fully ‚come up to scratch‘. The term ‚acceptance‘, on the other hand, is perhaps more appropriate for an understanding of true equality between differing people, i.e. the non-application of a yardstick on the part of the perceiver.

2.4 The interface between different cultures

As explained above, cultural interfaces arise wherever different cultures meet, and these interfaces can often be full of misunderstandings and conflicts. A cultural interface can exist between groups, between individuals or between representatives of cultures – regardless of whether those involved are conscious of the fact that the interface is a cultural one or not.

It has also been explained that ethnic cultures are only one example of the many types of culture that exist, and that cultures are not necessarily bound to geographical territory. In fact, cultural interfaces arise all over the world whenever people with differing perception- and value-systems meet.

This can be the case:

- within families, even members who live in the same house;

- within groups and societies of all kinds;

- in interactions between authorities, companies, nations;

- in interactions between individuals and authorities;

- between man and woman – or between men and women;

- between drug addicts and the police;

- between hunters and foresters etc.

In everyday interactions with other people, one is often unaware that one is operating at an interface between differing cultures.

The same is true of negotiations. People often think that they are merely involved in a case of ‚differing material interests‘. Few people realise that the difficulties they experience in trying to find a solution with someone who has different interests are caused by something more fundamental, i.e. differing perception- and value-systems or ‚deep-cultures‘.

When such situations turn into conflicts, people often find it difficult to remain in an objective mode of interaction. Emotions come to the surface which cannot be harnessed by rationality. Differences between deep-cultures create dynamics on multiple levels.

Perhaps it is going too far to suggest that every person who has a position of responsibility at a cultural interface should possess a high level of intercultural competence. On the other hand, it is clear that a strong awareness of the role of perception- and value-systems in everyday interactions would be beneficial to people in relationships of many types. One could argue that this should be mandatory for people who carry large amounts of social and material responsibility on behalf of others, e.g. high-ranking people in international organisations, in politics, in national and local administrations, in religious organisations and charities – as well as police officers, judges, politicians, teachers and managers of all kinds. However, the results of numerous surveys indicate that the levels of social competence in these functions are alarmingly low – which means that the levels of intercultural competence cannot be very high either (see Section 4.2).

3. Challenges at the interface between cultures

3.1 What are the particular challenges?

When conflicts occur at cultural interfaces, major challenges arise in relation to:

- overcoming the presence of ‚demarcation walls‘ on both sides;

- establishing the true source of the conflict which is hidden in the interaction between the deep-cultures;

- the surfacing of emotions and the uncontrollability of dynamics within groups;

- the unavoidable misinterpretation of intentions (see Sections 3.2, 3.3);

- a strong reticence to create new, commonly shared perception- and value-systems for fear of giving up one’s own identity and ‚raison d’être‘.

3.2 Why is it so difficult to overcome interface conflicts?

Interface conflicts are particularly difficult to resolve because of their multi-dimensionality and because of the lack of one-to-one correspondence between the underlying deep-cultures on each side.

This means that people like intercultural managers cannot apply a simple, structured approach when faced with a conflict which needs resolving. Instead, they have to induce and nurture a resolution-process on various levels and at various speeds.

For intercultural managers who are actual members of one of the cultures involved, the challenge can be very high. They need to be aware of their own deep-culture and thus be able to step back from it, i.e. to escape from their own ‚cultural prison‘ first of all. They must also be able to think themselves into the other deep-culture(s) involved, and then to mediate neutrally between them.

One of the major hurdles in the resolution of intercultural conflicts is the fact that the parties involved tend very often to misinterpret each other’s intentions (see Section 3.3). When two perception- and value-systems meet, it is almost inevitable that each party misunderstands the behaviour and motives of the other. The reason is that each party is preprogrammed to process the behaviour of the other according to its own structuring system. Research into cultural conflicts reveals – at their core – a complex set of perceived intentions, each of which is the outcome of inevitable misinterpretations and bears no resemblance to the original intentions of the other party at all.9

Overcoming this phenomenon is not easy because the intercultural manager has to lead the parties involved to the insight that what they have perceived in their own reality up until that point is merely the product of their own perception- and value-system, i.e. a self-induced illusion. This is the reason why many people who have experienced cultural conflicts firsthand say afterwards that they have learned even more about their own cultures than they have about others.

Bearing in mind the difficulties which can arise later in intercultural relationships concerning reciprocal intentions, it is crucial for intercultural managers to enquire at the outset into the aims of the representatives of the cultures involved. These aims need to be made transparent and sometimes to be modified as time progresses. If it turns out that the respective aims of the parties can be categorised as merely self-preserving, self-confirming and/or self-profiting, then the relationship is likely to run into serious danger, if not into disaster. The task of the intercultural manager is to lead the parties to the insight that their main goal must be to learn with and from each other. Only in this way can synergies develop between different cultures, and only in this way can the pre-programmed misunderstandings, destructive conflicts and costly breakdowns be avoided.

3.3 Two examples of intercultural conflict from real life

3.3.1 An interface between two departmental cultures.

At an English company called XX Ltd., there was a Controlling Department which had the task of monitoring all the output and costs generated by the other departments in the organisation. Over the years, a culture had developed in this department which placed a lot of value on detailed and accurate information. This applied both to the giving and the receiving of information. The head of the department saw it as being his responsibility to avoid all uncertainties whatsoever.

The task of the PR Department, on the other hand, was to handle the company’s image in the marketplace. In this department, a lot of value was placed on creativity, flexibility and spontaneity. The lady running this department rewarded people who succeeded in influencing specified target groups.

The departmental heads met regularly at management meetings and this is where the interface between the two departmental cultures became particularly noticeable. The head of the Controlling Department would complain about his colleague’s non-cooperation policy: ‚She doesn’t act in the interests of the organisation … She consistently fails to deliver the information on time … and it is never in the necessary quality or quantity.‘ In return, the head of the PR Department would criticise her counterpart’s extremely mistrusting attitude: ‚He is quite clearly out to improve his own standing in the company at the expense of the rest of us … He is deliberately destroying the team atmosphere among us senior managers.‘

Interactions like this one occur in many organisations, and often they are made more complex by the presence of differences in personality structure and in thinking-style, alongside the cultural ones. In the case described, the two departmental heads needed help to realise that they had been misinterpreting each other’s behaviour and motives. To a neutral outsider, it is obvious that each person had been using their own set of values in interpreting the behaviour of the other. However, reaching a point where both could stand back from their views about each other was difficult because both parties were highly conscientious people who put considerable energy into fighting for what they believed in. It is almost paradoxical that two motivated, conscientious colleagues can’t interact without major conflict, but it is a situation which is quite common. Many conflicts of this type end in disaster for at least one of the people involved.

As soon as situations like these arise, it is wise to draw fairly quickly on the resources of a colleague, a senior manager or anyone else who has sufficient intercultural competence to decode the situation and help resolve the conflict. The person providing this help would need to coach the relationship between the two departmental heads into a form whereby the interface no longer suffers, but becomes a source of synergy. The employees in the respective departments should also be able to profit from the resulting synergy between their managers.

3.3.2 The interface between two ethnic cultures

A large German-American company called ‚G-A‘ entered into a joint-venture with a successful company in Turkey called ‚T‘. The joint-venture was to be situated in Turkey and each party owned 50% of the new company.

‚G-A‘ selected three Germans and two Americans to take on certain mutually agreed managerial functions in Turkey. These managers had already proved to their employer that they had initiative and could operate well on their own; they were all technically well-qualified and had been identified as high achievers.

‚T‘ had a management team of ten long-standing members who all accepted the decision made by their boss to enter into the joint-venture with ‚G-A‘. The boss of ‚T‘ went to a lot of trouble to inform his managers about the venture and to answer all their questions. Caring for relationships was an important part of their company culture; they always acted as one, and showed immense loyalty to one another; authority was earned according to seniority and to one’s number of years of service to the company.

The joint-venture got off to a good start. The Turkish managers found nice homes for their counterparts‘ families to live in and helped them to feel comfortable in their new environment.

After a short time, however, cracks began to appear in the new management team. The managers from ‚G-A‘ complained about the deliberately non-cooperative, inflexible and conspiratorial behaviour of the Turks. The latter were somewhat reticent to talk about their problems with their boss, but were convinced that the ‚G-A‘ people were deliberately lying; they felt that they were consciously undermining traditional ways of doing things, that they were each out to prove how competent they were, and how much they could change in as short a time as possible. On top of this, the Turkish managers regarded it as an insult that ‚G-A‘ had sent such inexperienced and egoistic people.

Careful decoding of the various perceptions again revealed that each party had been processing the behaviour of the other in terms of its own perception- and value-systems.

Decoding of this type can be done using insights from the well-published research into cultural differences. The work of Hofstede, for example, offers the deep-cultural dimensions of ‚power distance‘, ‚uncertainty avoidance‘, ‚collectivism-individualism‘ and ‚femininity-masculinity‘. All four of these dimensions can be found to be active in the case-study above.

Hofstede defines them as follows:

the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organisations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

the opposite of individualism; together they form one of the dimensions of national cultures. ‚Collectivism‘ stands for a society in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive ingroups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him or herself and his or her immediate family only.

the opposite of masculinity; together they form one of the dimensions of national cultures. ‚Femininity‘ stands for a society in which social gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

stands for a society in which social gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focussed on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.10

Using these dimensions to decode the perceptions and value-judgements in the case-study, there are already a number of clues in the limited amount of information given: ‚T‘ has a higher power distance and uncertainty avoidance than ‚G-A‘. The latter, on the other hand, has a higher individualism and a higher masculinity than ‚T‘.

It was the inevitable perception clash between these two deep-cultures which led each party to generate a negative picture of the other’s intentions. The latter then became the reality of each perceiver, even though – as they discovered in the resolution process later – none of these intentions were present in the minds of those being perceived. The dynamics of such a process of ‚perceived-reciprocal-intent‘ and how it can escalate into a highly destructive conflict is described in more detail elsewhere.11

Again, to help resolve this type of conflict, a neutral intercultural manager is needed in whom both parties can confide and who possesses the level of intercultural competence needed to decode the various perceptions and value-judgements from a deep-cultural perspective.

4. Selecting people for an intercultural management position.

4.1 The ideal profile

In what has been discussed so far, a number of indications have been made concerning the key qualifications which are needed for an intercultural management position. For example, a fundamental acceptance of different-ness, a lack of prejudice, an ability to stand back from one’s own perception system etc.

Combining the results of studies by several researchers, two sets of qualifications can be set up. The first set is needed for managerial functions where the person has a responsibility for the interface between different cultures of any kind, except ethnic cultures which use different languages. The second can be treated as an additional set of qualifications which are needed in the case of the latter.

4.1.1 Ideal profile for all intercultural managers

The most important character traits

- honesty to self

- respect towards others

- striving towards veracity

Preferred thinking-style

- flexible, non-categorising

- holistic

- able to create syntheses

Necessary attitudes

- positive attitude towards life and human beings

- genuine acceptance of people different to oneself

- freedom from assumptions and prejudices

- willingness to listen openly to others

Necessary abilities

- receptive and articulative communication skills

- ability to mediate

- ability to stand back from one’s own perception- and value-system

- ability to think oneself into differing perception- and value-systems

Necessary knowledge

- knowledge of the subject at-hand

- knowledge of surface- and deep-culture

Experience

- well-processed experiences from relationships with other people, i.e. personal involvement in conflicts of personality-structure and culture

4.1.2 Additional qualifications for intercultural managers working with people from different ethnic cultures with differrent languages

Linguistic abilities

- fluency in the languages of the people involved

Experience abroad

- well-processed experiences from living in other ethnic cultures, i.e. optimally in widely differing ethnic deep-cultures

4.2 Why do so few people possess the appropriate abilities?

Studies have shown not only that the levels of social and intercultural competence among managers in Europe generally are much lower than they need to be, but also that these levels are on the decline.

This automatically raises the question as to why this is the case, especially when one considers that increasing numbers of young managers receive quite intensive exposure to the social sciences as part of their education. Perhaps, however, it is precisely the approaches used in the social sciences which are in part contributing to these declining levels.

Social and intercultural competence are attitudes towards other people. As such, they are not learnable techniques. One cannot force these attitudes upon oneself or upon others if they are not already present. This, in turn, means that they are not easy to acquire and develop. The special methods which can be used are explained below (see Section 5.2).

Social and intercultural competence differ from the more technical kinds of skills in that the latter can be acquired through applying the principle of ‚to know‘, i.e. to know something or to know how to do something. This principle is sometimes termed the ‚how to‘ approach. The sciences – and the premises upon which they are built – are a central departure-point and a constant point of reference for the acquisition of technical skills. In order to develop social and intercultural competence, on the other hand, the principle of ‚to know‘ needs to be replaced by the principle of ‚wanting to understand‘.

The principle of ‚to know‘ vs ‚wanting to understand‘

In order to clarify this distinction, the principle of ‚to know‘ operates in a binary, cartesian way, i.e. either one knows something or one doesn’t; something is either proven or not; if something cannot be measured and empirically tested, then it cannot be captured scientifically or ‚known‘. In this tradition, learning is an activity with the end-point, e.g. an examination, of establishing if things are ‚known‘ or not.

The principle of ‚wanting to understand‘, on the other hand, does not make recourse to a definable end-point. One never assumes things about individuals or groups; one never purports to know them; one never seeks to boost one’s personal confidence in situations by gathering generalised information about people in advance; one never assumes that one knows the issue or the answer; one is fully aware that one will never be able to fully understand another person but always willing to try. The following story serves to illustrate:

Contemporary education in western societies is based largely on the principle of ‚to know‘ and on the premises of ’science‘. (In fact, the two terms are almost equivalent, the former finding its way into English through Old Norse and the latter from Latin.) The same is true of the social sciences, which have been made to conform to dualistic, cartesian premises just like all other ‚disciplines‘. The social sciences have the objective of treating the phenomenon of the ‚human being‘ in scientific terms, i.e. as a pure ‚object‘.

Most approaches to ‚management‘ follow the same principle. They seek to treat the ‚objects‘ of management, whether these be organisations or people, in such a way that they can be managed. Management therefore deals with objects – all of which are, by definition, outside one’s own person. The latter remains untouched and need not be changed, nor made to fit, nor made to dissolve. To do so would contradict the central premises of management. ‚To manage‘ means to change and master the outside world without having to become one with it. Self-management is a popular but strange concept which contains the inherent contradiction of converting the subject into an object in order to change it.

Within these science-based approaches to management, one finds highly creative methods of mastering the outside world. Vast numbers are imported from the field of psychology like transactional analysis and neuro-linguistic programming. The result is that the people who receive managerial education take away with them – often unwittingly – highly refined ways of manipulating their employees. It is not surprising, therefore, that the levels of social and intercultural competence are on the decline.

Intercultural management is something which differs strongly from traditional management. In being concerned with facilitating commun-ication and synergy between differing cultures, it requires a full internalisation of the consequences of deep-culture-interfacing. Each perceived ‚object‘ is nothing but a self-referential creation by a subject. This means that it is absolutely impossible for the member of one culture to accurately interpret the behaviour and motives of someone from another culture.

Neither the interfaces between cultures nor cultures themselves can be ‚managed‘ (in the traditional sense of the word).

5. Education and training in ‚inter-cultural management‘

5.1 The objectives

In order to equip people to take on a position at a cultural interface, one has to develop the qualifications which were outlined above in the profiles for intercultural management (see Section 4.1). It is evident that certain aspects involve major personality development.

The following objectives characterise this kind of personality development:

- the candidates should reach a stage of inner integrity (or ‚wholeness‘), which means that their interactions with others are a true expression of their real core personality. In order to achieve this state, it is necessary for them:

- to experience the real core of their personality, in order then to go on and work with it;

- to experience, internally process and resolve any disharmonious and stress-creating aspects in their behaviour which could otherwise negatively affect their interactions with other people, and which could become interference factors when they have to mediate at cultural interfaces.

- they should experience their own perception-system and its boundaries. By doing this, they will be able to work at the mechanisms which they have acquired in the past and which determine their acceptance of different-ness in other people, i.e. their social and intercultural competence.

- they should experience their own creation of value-judgements and process their respecttive origins.

On the basis of these experiences, they should automatically begin re-processing their previous interactions with people who differ from themselves. This will lead them to gain new insights into those interactions.

- they should work at their ability to accept uncertainties, ambiguities and dilemmas and to process them as a part of themselves without looking for quick solutions using rational, externalising methods.

- they should become acquainted with the challenge of ‚mediation‘, i.e. being present in both an active and a passive way during a process of conflict-resolution and synergy-creation.

5.2 The methodology

The objectives which were outlined in Section 5.1 and many of the key qualifications in Section 4.1 cannot be achieved through a cognitively-based acquisition of knowledge.

It needs also to be stressed that a personality-development process of this kind can only be undertaken if the person concerned is willing. Of course, intercultural management involves so much social and material responsibility that only those people can be considered for such a position who fulfil certain criteria to begin with and who show the willingness to develop their personalities in this way. Assuming that certain criteria are fulfilled at the outset, a process of increasing awareness can be initiated. This process needs to be carried out with groups of people, optimally with between five and eight. Using specially-designed exercises, the participants discover how they perceive the world and how they create value-judgements about what they perceive. At the same time, they experience that other participants perceive the world – and judge it – differently. These experiences then lead each person to a whole new set of insights about the inner and the outer world, and in many cases to a marked change in attitude towards other people. They begin working at their own interfaces – which is a precondition for working at the interfaces of other people.

It is essential that the speed of this process is determined by the participants undertaking it and that each participant has the opportunity to develop their social and intercultural competence at their own pace. Self-development should be catalysed in a non-manipulative way, using the co-presence of people who are different to each other. If the process is conducted in the appropriate way, most participants can begin to attain marked attitudinal changes within three to five days.

In some cases, participants will display a tendency to process their experiences ‚in their heads‘ which prevents them from really internalising what is going on. The person who is coaching the participants‘ self-development needs to be aware of such tendencies and to help participants like this to process the experiences in a more holistic and subject-quality way. The principle of ‚wanting to understand‘ needs to be central in the whole development process. This means that one should use minimum quantities of empirically-gathered data, scientific models, dualistic categorisations etc.

By the end of the development process, the participants should have made themselves aware that:

- they will never be able to fully understand others;

- it is extremely difficult to put oneself in the position of another person;

- it is wise never to make assumptions about other people or cultures;

- they will in future repeatedly catch themselves out for having misinterpreted what they have experienced;

- they will nevertheless never want to stop trying to understand other people.

References

- See Faure, G. & Rubin, J. eds, Culture and Negotiation, Sage, London, 1993 (Pages 227-8) (back)

- For an overview of the definitions of ‚culture‘, see Münch, R. & Smelser, N., The Theory of Culture, University of California Press, 1992. For an examination of ‚culture‘ in relation to the world of business, see Schafer, D., em>Cultures and Economies – Irresistible forces encounter immovable objects, in Futures 1994 26(8) (back)

- See Rock, I., em>Wahrnehmung, Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Heidelberg, 1989 (back)

- See Hofstede, G., Cultures and Organisations, McGraw Hill, London, 1991; also Hampden-Turner, C., The Seven Cultures of Capitalism, Doubleday, London, 1993; also Trompenaars, F., Riding the Waves of Culture, Economist Books, London, 1993 (back)

- See Robinson, S.D.G., The Selection, Training and Coaching of Managers for Cross-Cultural Projects and Business-Ventures, in Barometer, 1/93 (back)

- See Robinson, S.D.G., Der Global Manager: Mangelware, in ManagerSeminare Nr 11, April 1993 and in Barometer 4/93 (back)

- See Robinson, S.D.G., Who’s Afraid of Intercultural Competence, in Barometer 1/93 (back)

- See Herrmann, N., The Creative Brain, Brain Books, N. Carolina, 1989 (back)

- See Morosini, P., The Importance of Cultural Fit in Cross-Border Merger and Acquisition Deals, in Barometer 4/93 and Lichtenberger, B. & Naulleau, G., French-German Joint Ventures: Cultural Conflicts and Synergies, in Barometer 1/94 (back)

- See Hofstede, G., Cultures and Organisations, McGraw Hill, London, 1991 (back)

- See Robinson, S.D.G., The Fundamental Question of ‚Intent‘ in Joint-Ventures and Acquisitions, in Barometer 3/93 (back)